#MeToo and Time’s Up Movements Continue Their Onward March

How Much or Little Has Changed In a Year

February 21, 2018

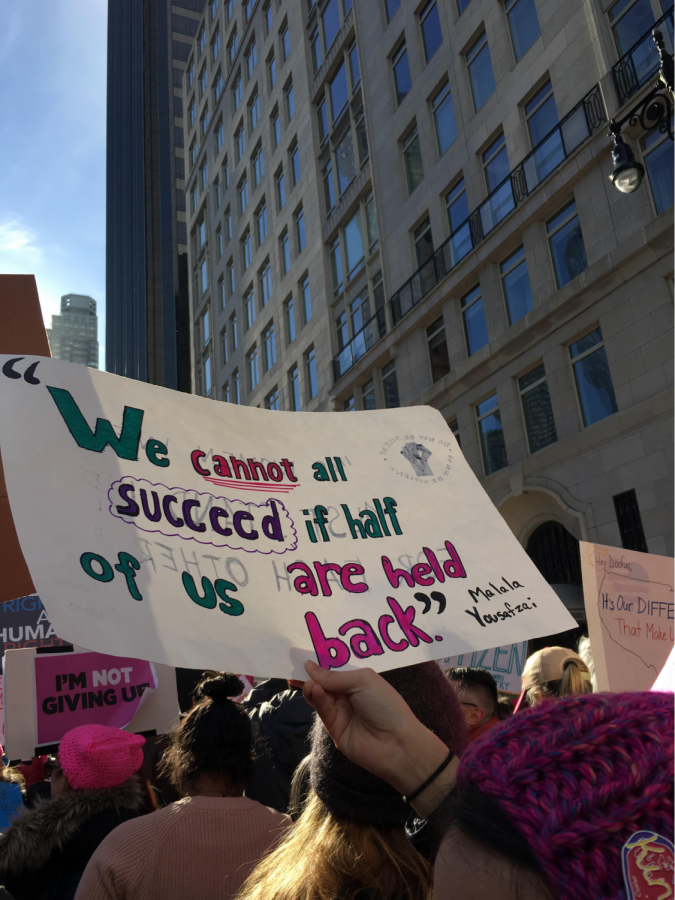

In the last issue of Bear Facts, we examined the growing #MeToo movement and how male abuse of power has permeated our culture, workplace, schools, and many of our own lives. In this issue, we continue our examination of this movement by looking at its evolution over the past year and the roots that underlie our current words and actions. Our correspondent reports from NYC’s 2nd annual Women’s March.

It all started with this statement: “You can do anything. Grab ‘em by the p***y. You can do anything.”

On October 7, 2016, this video from Access Hollywood was released by the Washington Post and NBC News. The video was taken in 2005, and it was a recording of a casual conversation between Donald Trump and the show’s producer, Billy Bush. When it was eventually released, Trump’s attitudes about women became clear.

Then, America elected him as our 45th president.

This sparked outrage, prompting many women to quickly take action against Trump’s objectification of women and blatant sexism. Right after the election on November 8, plans for the Women’s March on Washington began, and so did sister marches in the rest of the country. Although the march was scheduled to be held the day after Trump’s inauguration, it was not focused toward Trump, but rather toward the divisive culture in America.

Flash-forward to October 2017, when movie producer Harvey Weinstein was accused of sexual harassment. The #MeToo movement began, changing the way we talk about sexism, sexual assault, and the abuse of power. People of all different races and genders were coming out and declaring that they’d, in various ways, been affected by male privilege and directly challenged the system that we’ve put in place. The #MeToo movement grew into Time’s Up, founded on January 1, 2018. The basis of the Time’s Up movement is to address systematic inequality in the workplace, focusing mostly on sexual harassment.

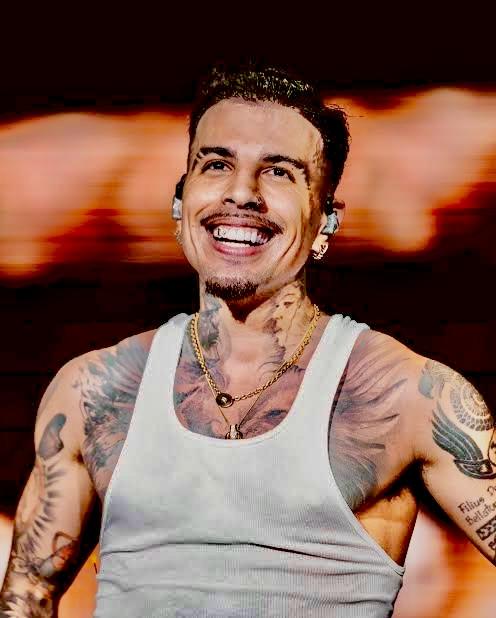

However, the discussion around sexual assault became more complicated when news broke out involving Aziz Ansari. The story is that a woman (given the name “Grace” in the article where the story first appeared) went on a date with Ansari that quickly went sour and, in her mind, resulted in non-consensual sex. This story quickly resulted in a dichotomy of opinion. Many women responded, saying that they had faced a similar situation where they had been pressured to do something they did not want to do by a man who held some type of power (whether it be money, celebrity, or simply having an advantage). Others were outraged, believing that Ansari couldn’t be expected to be a “mind reader” because Grace had said “yes” (albeit after feeling pressured) and that he had been unfairly slandered by the article.

Here is where we find a problem with figuring out a solution to sexual assault. How do we know what it is? In the case of Ansari, we have two wildly different stories of the same night. The problem doesn’t just lie with people like Weinstein anymore–now, it lies within America’s culture. We give men power over women, whether we’re aware of it or not, through the way we discuss and educate people about things like sexual assault or discrimination. Men don’t have privilege because they earned it; they have privilege because they know how to use their power even if they don’t realize it.

This is what people were marching for on January 20, 2018. Yes, there were people there for reasons that were different than this reporter’s–the government shutdown, DACA, and other policies with which they were unhappy. But I did experience a camaraderie against male entitlement, especially when it came to topics like our president or the recent purge of sexual assailants. The Women’s March of 2018, for me, was about protesting the glaring bigotry that resides in our culture and in the White House that people have been ignoring for so long. Sexism has been a big deal since the beginning of time, and it has infested our development and behavior more and more, yet we have been ignoring it. Many people don’t see what is wrong: they can identify rape as a problem, yes, but when it comes to subtler phenomenon (such as how often women apologize) we seem to be blind to the caste system we have created.

Our culture is not a result of people like Trump, it is the other way around: people like Trump are the result of our culture. It’s our responsibility to speak up and change it.