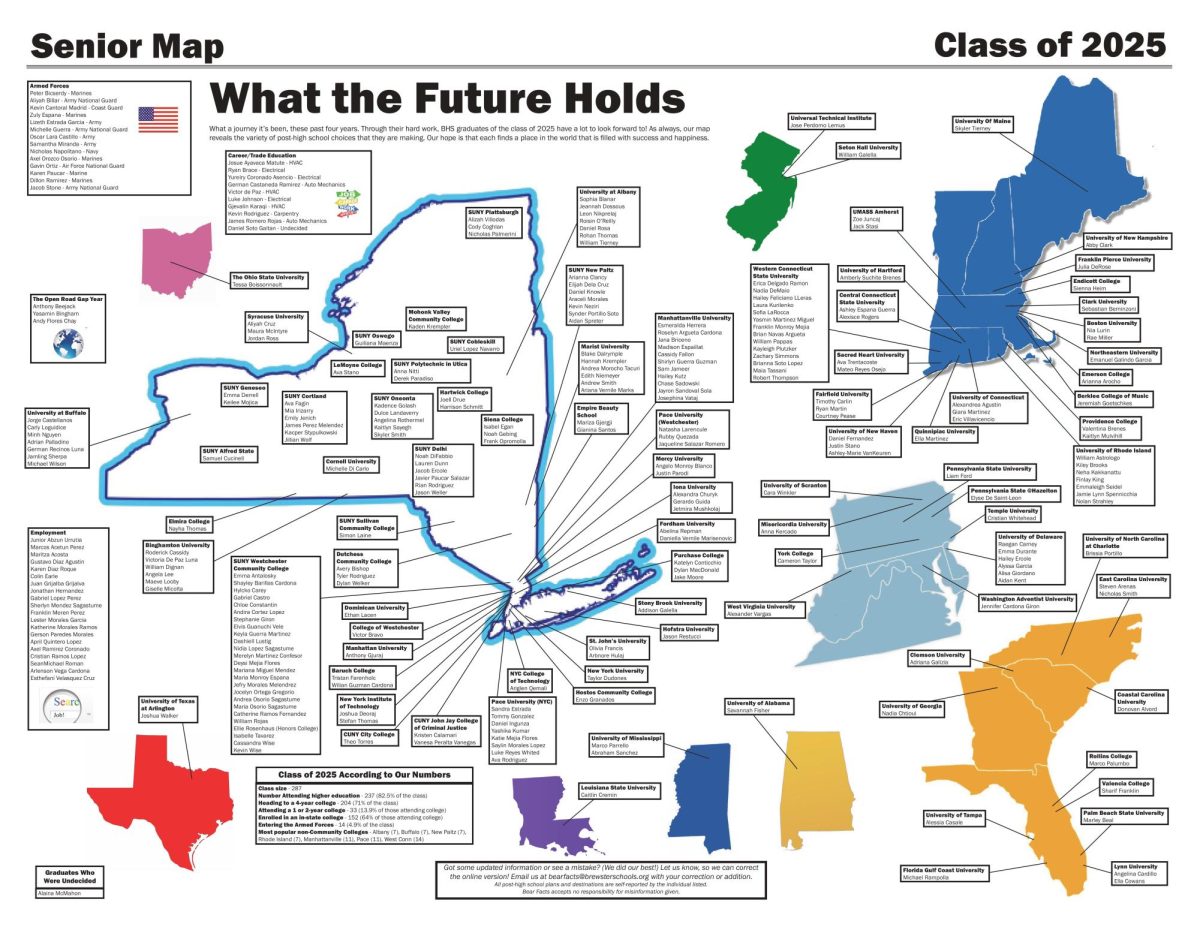

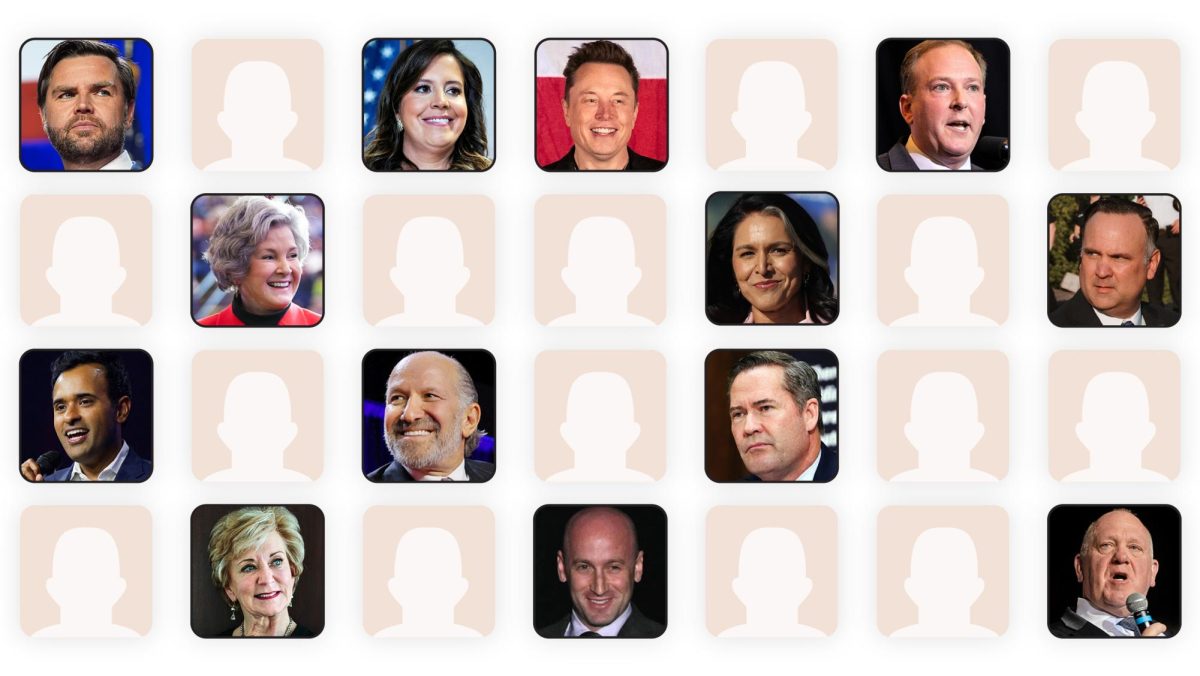

For many years, there has been a great debate regarding the origins of the name of Lake Tonetta in the Town of Southeast in Putnam County, New York. During this time, Lake Tonetta, also known as Tone’s Pond or Waring’s Pond, has been associated with a great deal of folklore without confirmation of the historical landmark’s namesake. It was often suggested that the lake was named after Tone, an enslaved Black man who was promised his freedom by Southeast resident John Waring in exchange for his service in the Revolutionary War. However, the only information recorded in local histories is that sometime after the Revolutionary War, Tone and his wife Etta, who was said to be “half Indian, half Negro,” settled at the lake, running a fisherman’s tavern and leaving behind a quite “numerous and respectable number of descendants.”

Although it was easy to accept that the lake was named by fusing together the names of Tone and Etta, local histories never cited primary sources, and thus, folklore became the accepted truth of the town. It was hoped that a review of the National Archives’ Revolutionary War records would help confirm that Tone had served in the Revolution, perhaps under his enslaver’s last name, Waring.

What was discovered about Tone, however, was much more impressive than just being the namesake of a local lake.

First, it should be noted that there aren’t any Waring manumission records (documenting the freedom of a formerly enslaved person) that have surfaced to date. Moreover, Tone and Etta’s names cannot be found in any local census records following the Revolution.

While reviewing historical records from the period, it was impossible to locate a “Tone Waring” until it was realized that “Tone” was perhaps more of a nickname which could be associated with the name Tony or Anthony. Therefore, when working through the transcription of pension files of Revolutionary War Service as part of the Citizen Archivist Mission with the National Archives, Anthony Waring’s name jumped right off the page. (Importantly, of John Waring’s nine children, five of whom were male, none were named Anthony.) This discovery supported the accuracy of the local folklore.

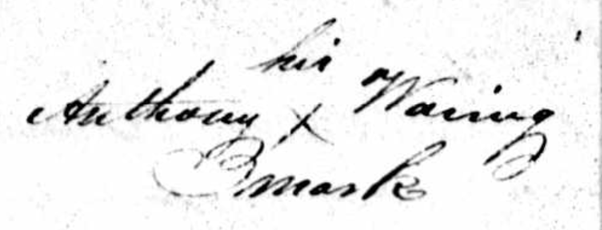

With over 22 pages of records in his pension file, it is well documented that a man named Anthony Waring, from the Town of Southeast, initiated the pension process for his service following the creation of the Revolutionary War Pension Act of March 18, 1818. As early as April 6, 1818 (with the assistance of Jonathan Morehouse Esq., a then-acting judge of the Court of Common Pleas in Putnam County), Anthony Waring signed his pension application with an “X,” referred to as “his mark,” indicative of a man who could not read or write.

But how could one be sure this was actually the “Tone” of Lake Tonetta?

Following his death in 1821, Anthony Waring’s wife, Mahettable, (also referred in the documentation as Hetty, and perhaps as “Etta”), pursued the widow’s pension with the assistance of Ebenezer Foster, Esq., then-judge of the Court of Common Pleas for Putnam County. This was not possible until July 4, 1836, after Congress passed legislation allowing qualifying widows of veterans to make a claim, providing that they were married to said veteran, and remained unmarried after their spouse’s death.

Local newspaper archives document Tone and Etta’s descendants living in both the Town of Southeast and the Village of Brewster for several generations up through the early 20th century. In fact, many of these descendants were some of the earliest free Black families to purchase property in the Town of Southeast. In 1836, Charles Hutchinson and his son Orrin — Tone and Etta’s maternal grandson — purchased a farm at the base of Turk Hill Road, just outside the Village of Brewster. Tone and Etta had six children, one being Jane, who later married, taking on the name Jane Hutchinson.

In Mahettable’s widow’s file, further details about Anthony Waring are provided by Jane’s testimony. Jane states that her parents, Anthony and Mahettable, lived together as husband and wife, raising six children. She also attested to her parents’ inability to read or write and recalled being with her father when he received some of his earlier pension money (likely part of the 1818 Pension Act). Following Anthony’s death on July 15, 1821, Mahettable was left destitute and lived with Jane’s family. By that time, Jane and one sister were Anthony and Mahettable’s only surviving children. Jane was likely married to Charles “Hutchinson’’ and was the mother of Orrin, who purchased the previously mentioned Turk Hill property.

Further testimony for the widow’s pension came from Town of Southeast resident Isaac Paddock, who was well acquainted with Anthony Waring and his stories of service in the Revolution. He helped to document Anthony and Mahettable living as man and wife in the Town of Southeast as early as 1777 and stated that Anthony and his wife originally came from Long Island.

The next document in Anthony Waring’s pension file was the testimony of 84-year-old Mary Waring, a town resident of over sixty years and neighbor who stated that she too was well acquainted with Anthony and Mahettable for over forty years. Mary was the second wife of John Waring who resided in the old homestead which, according to William S. Pelletreau’s “History of Putnam County, New York” [1886], was a tenant farm located:

North of Southeast Center, and adjoining the north part of Lot 9 (of the Philipse Patent) . . . which ran west to what was then called Waring’s Pond, and now known as Lake Tonetta. It was more generally known as “Tone’s Pond,” from a negro who lived near it.

Today, residents of the Town of Southeast know this as the area encompassing Brewster Hill, Minor Road, Shore Drive, and parts of Tonetta Lake Road. This was yet another factor validating town folklore, connecting Anthony Waring to the naming of Lake Tonetta, further suggesting that stories about Tone and the lake were true.

In the pension file there is also a document from 1836 in which Mahettable Waring, 97 years old, swears an oath to her testimony detailing that she and Anthony were married about 1773 by a minister of the peace in “Smith Town”, Long Island. In her testimony, marked with an “X” or “her mark,” she mentions their six children and Anthony’s service in the Continental Army.

One of the final documents in the file is the court clerk’s recorded copy of a pension file dating back to April 1818 citing “Anthony Waring, aged eighty four years, a man of color & resident in the town of Southeast…” Significantly, this is the first and only time Anthony is referred to by his race in his Revolutionary War records. These documents confirm that he is a Black Revolutionary War veteran and therefore, the neighbor likely enslaved by John Waring.

In his recorded oath, Anthony declares that he enlisted in Danbury, Connecticut, with Captain Comstock’s Company as a private soldier. Within one month, he was transferred to Captain David Bushnell’s Company, who also happens to be the early inventor of the submarine “The Turtle”. They went to the “Highlands of New York” where Anthony was made a Private in General George Washington’s new Corps of Sappers and Miners, a mixed racial force.

Service records for Anthony Waring, contained in the Revolutionary War Rolls, confirm his commencement of service on June 1, 1781, with the officers and men of the Sapper and Miners from the quota for the State of Connecticut.

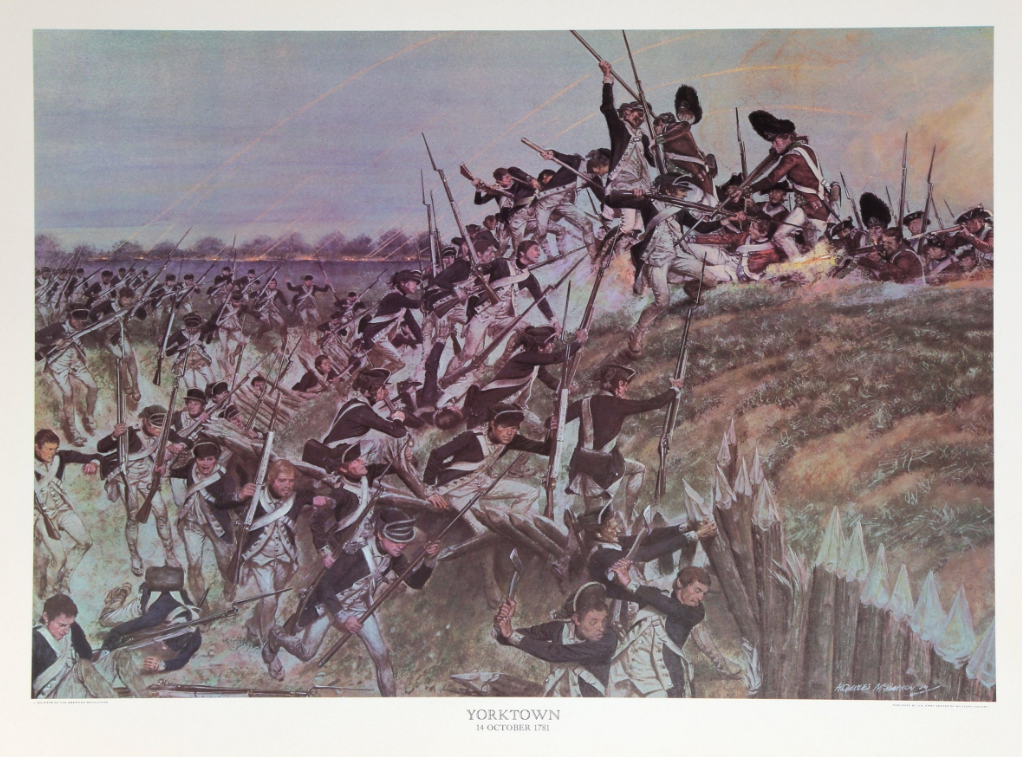

By the fall of 1781, Anthony, a.k.a Tone, according to his affidavit, “was engaged in cutting away the pickets at the storming of one of the redoubts near Little York,” what we know today as the patriots’ siege of the Battle of Yorktown. Tone also stated that he assisted at the capture of General Charles Lord Cornwallis, marking the American victory in the War for Independence.

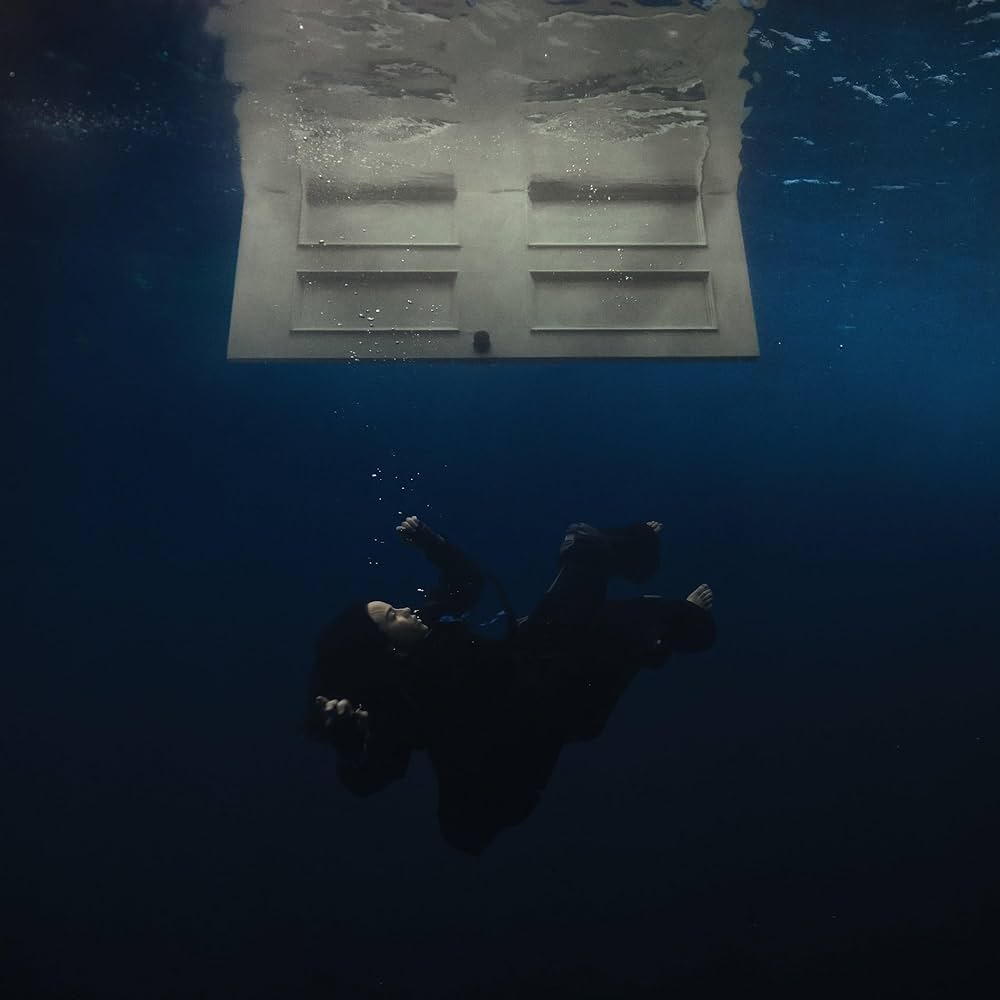

Interestingly, the U.S. Army Center of Military History has a 20th century painting by H. Charles McBarron, Yorktown, 14 October 1781, in which a dark-skinned member of the Sappers and Miners can be seen cutting away the pickets during the battle, perhaps a depiction of Anthony Waring. (See above painting)

Anthony Waring served for three years during the American Revolution with the Sappers and Miners until his discharge at West Point at the end of the war. His certificate of honorable discharge was signed by the “Honourable Major General Knox, Commander of the American Forces on Hudson’s River,” and noted as recorded in the Book of the Regiment by D. Bushnell, Capt.

In April 1818, Anthony Waring received a certificate for a pension of eight dollars per month. He was recorded as suffering from old age, lameness in his leg from service in the war, partial deafness, and stating that, “I am utterly unable to earn my subsistence by labor, that my family counts only of myself and my wife Hetty, aged seventy six years, unable to support herself through old age.” He stated his most recent occupation had been a broom and basket maker and held no real estate with his personal estate consisting of the following: one old table, four chairs, one chest, one cupboard, one stand, one looking glass, five plates, one platter, one tea pot, three tea cups and saucers, three bowls, three spoons, a few pots and pans, a fire shovel and tongs, four baskets, one dog, one cat, and two hens.

Anthony received his soldier’s pension from 1818 until his death in 1821. Thanks to continued petitions and claim acts through the 1830s, Mahettable was awarded his pension in arrears, for over $400 in 1836 — the same year her daughter’s family, the Hutchinsons, were able to purchase property in the Town of Southeast.

In the beginning, this research was undertaken simply to determine whether the local stories about the naming of a local lake were true. What was discovered, with the help and guidance of others, was something much more significant. It is the story of an enslaved man who fought for the freedom of this country, who ultimately obtained his own freedom and whose Revolutionary War pension arguably enabled his family to be some of the earliest, if not the first, Black owners of property in the Town of Southeast, Putnam County, New York.

Now, thanks to the transcriptions of Citizen Archivist Missions, residents can officially pay tribute to “Tone” – the partial namesake of Lake Tonetta – and, more importantly, celebrate his heroism as a patriot at the Battle of Yorktown, where Lord Cornwallis’ surrender marked the end to the Revolutionary War and the freedom of our nation.