Your COVID Experience May Be Different from My COVID Experience – The Pandemic and POC

March 8, 2021

In 1932, the “Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male” was a study to record the history of syphilis, where 600 black men were involved (399 with syphilis and 201 without). The purpose of the program was to study and detail the natural history of syphilis in the hope of justifying treatment programs for blacks. However, the men had been misled and were not given all the facts required to provide informed consent. They were told that they were being treated for “bad blood” in exchange for free medical exams, free meals, and burial insurance. Yet, the men were never given adequate treatment for their disease. Even when penicillin became the drug of choice for syphilis in 1947, researchers did not offer it to the subjects, and the individuals in the study were not released from the study until 1972. I bring this topic up because People of Color have been misled numerous times when it comes to health: distrust towards the government and the healthcare system is very strong in the black community.

Aside from the medical aspect, social injustice was one of the highlights of this pandemic. After the protests and rallies, black men and women (mainly in southern states) were hesitant in wearing a mask because they feared getting racially profiled, being arrested, or even being shot and killed. A thought like this wouldn’t cross your mind if you aren’t a person of color, but due to unfortunate circumstances in the world, it’s a scary reality.

There is no question that COVID-19 has had a world-wide impact. We have all had to adjust how we live. Typical tasks such as going to work, to school, and grocery shopping require us to think twice and ask ourselves, “Do I have my mask?” and, “Is it safe?” While the impact has been felt by everyone, let’s focus on the seemingly greater impact on POC (people of color) during the past 11 months. We can not overlook that POC and lower-income families have felt a greater deal of disadvantages which have become even more magnified by COVID.

On July 24th, 2020, the CDC released an article titled “Health Equity Considerations and Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups” to pinpoint the fact that in the midst of a pandemic, “healthcare access can also be limited for these groups by many other factors, such as lack of transportation, child care, or ability to take time off of work; communication and language barriers; cultural differences between patients and providers; and historical and current discrimination in healthcare systems.” Access to quality healthcare remains a major problem for the majority of POC. From doctors dismissing symptoms to receiving minimum care, without access to quality healthcare, people of color will continue to receive the bare minimum and die with underlying conditions that would be treated effectively for anyone else. Statistics show that Black Americans have been dying at about 2.4 times the rate of white Americans. As medical anthropologist Clarence Gravlee put it in Scientific American: “If Black people were dying at the same rate as white Americans, at least 13,000 mothers, fathers, daughters, sons and other loved ones would still be alive.”

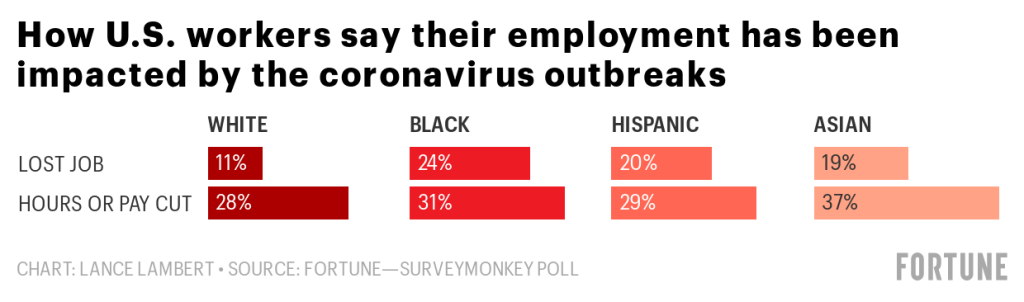

Once again, nobody is eliminating the hardships of anyone else, but something so minute as living in subsidized housing and being more likely to take public transportation to and from work plays a leading role in the increase of COVID-19 amongst POC and low-income families. Growing unemployment rates puts some racial and ethnic groups at a higher risk of getting evicted or unfortunately becoming homeless. POC are not well-represented in essential workplaces, so while other racial groups have the luxury of working from home, minorities are out working with the high chance of contracting COVID. There aren’t enough paid sick days to cover an employee for a whole year in the midst of a pandemic, so when employees call out, there is a constant fear that has been built up about losing their jobs.

But where we fall short once again is with the stimulus packages that have been administered and proposed. Let’s take a look at a typical POC family (mother and father with 2 young children) living in an apartment. In this family, the mother works as an Administrative Assistant in the school district and the father works as a local truck driver. One of the kids is a toddler who attends daycare and the other is a 2nd grader who attends paid after-school care. When the pandemic comes, mom’s office closes. She isn’t considered essential enough to work from home, so she loses her pay. Distribution has been halted and the dad is now home without pay. That’s 2 incomes lost with a home to still maintain where rent is $1700 for their 2-bedroom apartment (add another $300+ for bills, etc). The stimulus might help, but it clearly doesn’t help to the extent that they need it to.

While the employers and packages have fallen short, the government has initiated programs to identify and help POC. Low income families and POC began rapidly signing up to receive government assistance such as WIC and food stamps (SNAP). For those who are unaware, these benefits provide low income families with a monthly monetary balance on a card to pay for food at the grocery stores, so these individuals won’t have to come out of pocket especially when income is scarce. According to the Office of Temporary and Disability Assistance, “As of October, there were nearly 2.8 million SNAP recipients throughout the state, an 8 percent increase from the same month in 2019.”

Over the past year there have been immeasurable hardships but in a way they also opened doors for people to receive help they didn’t know was out there, or even overlooked for many years. Despite these gains, there are still so many ways in which our culture and our government should respond to crisis when it hits the POC community.